Have you ever taken a problem to a friend or colleague and they have made it all about themselves; either because of their own experience (relevant or not) or their reaction to your experience?

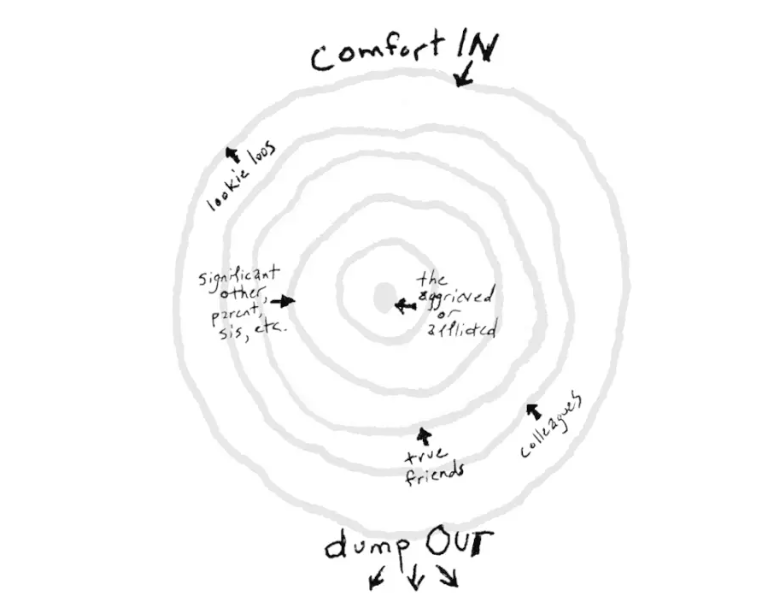

Based on concentric circles, Ring Theory (developed by Susan Silk) is a simple model for helping people to become better allies. At the centre is the person who is experiencing something difficult – a medical emergency, divorce, loss of a loved one, or some other traumatic event. The next few rings are for those closest to that person – their immediate family and life partners. Mid-range rings could be for friends and extended family. Outer rings are for colleagues, neighbours, and other parties who have a limited interest in this person’s affairs.

The model proposes that true allies offer support to those who occupy a circle nearer to the person at the centre than they themselves do. Venting or trauma-dumping can only be directed to those who occupy a ring further away.

In sum, you comfort in and dump out.

For example, say my mother is struggling with chronic pain. As her daughter, I occupy a ring very close to her. Obviously, I can best support her by offering comfort (acts of service, a shoulder to lean on). However, if I choose to make our time together about my reaction to her chronic pain, she isn’t going to feel supported and she may even end up comforting me. In this instance I would have dumped in. A better choice would be for me to share my anxieties about my mother’s situation with my good friend, freeing up my capacity to support my mother better.

I have previously shared this model with friends, as a way to conceptualise allyship in the face of discrete crises.

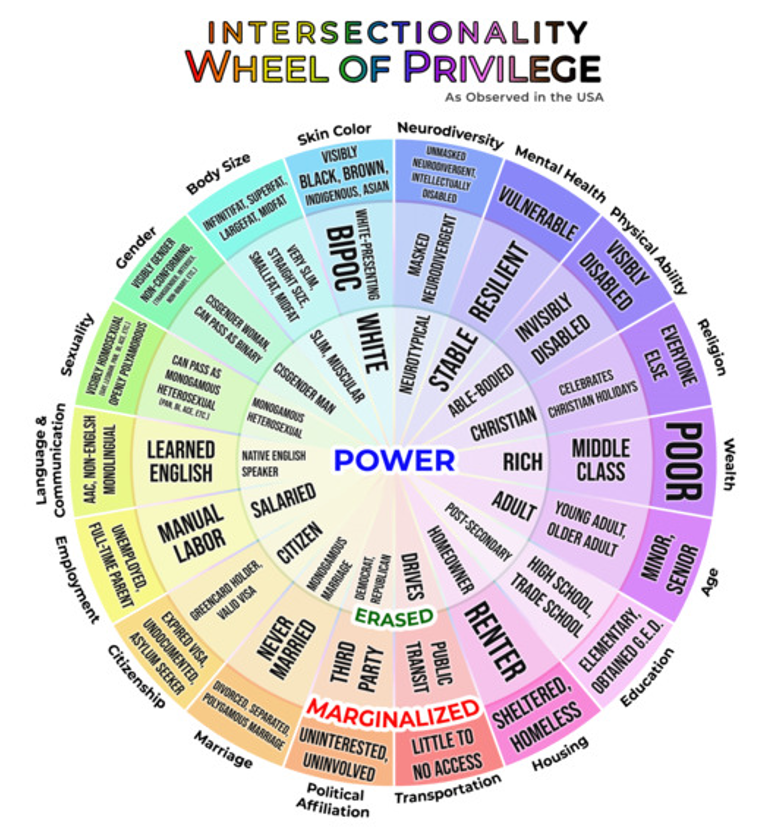

But lately it has occurred to me that this can be applied to any marker of privilege. The wheel below identifies 18 domains of privilege active in Western society: gender, body size, skin colour, neurodiversity, mental health, physical ability, religion, wealth, age, education, housing, transportation, political affiliation, marriage, citizenship, employment, language/communication, and sexuality. And there is probably scope to add a few more!

Applying Ring Theory to these domains, it would be tone-deaf for a person with wealth – or at least a stable, well-paying job – to gripe about not winning the lottery, not qualifying for a government subsidy, losing money on the stock market, or having to replace a broken item to a person experiencing financial distress.

And yet this happens all the time, in various settings, across the whole spectrum of privilege. A person with a chronic medical condition or disability may struggle to hear their friends constantly complain of minor ailments. Similarly, someone who has just been evicted isn’t going to want to hear about your distaste for cleaning your bathroom.

It’s often not the intention to invalidate the lived experience of those with less privilege, but that can definitely be the outcome. Over time, erasure of our experience can be incredibly painful and leave us feeling quite isolated.

I want to be clear that all people have the right to express their feelings or experiences, and have these heard and validated. The key here, as Ring Theory helps us see, is who we’re off-loading to. Of course there will be close relationships which have an imbalance in privilege. And it is only reasonable that the person with more privilege in a certain domain should be able to confide in those close to them. In these situations, a simple check-in could be helpful:

“I know you’ve got a lot going on with your health. Would it be ok for me to vent about my headaches? They’ve got me a little worried.”

For those who experience erasure or marginalisation in any domain, this acknowledgement goes a long way.

Image credit: Wes Bausmith / Los Angeles Times